Fundamentals of absorption spectroscopy

Fundamentals of absorption spectroscopy

Foreword: Hello everyone, in the last issue, I led you to understand the origin of absorption spectroscopy, and today I will lead you to learn the basic physical principles of absorption spectroscopy. Due to the limited level of authors, please actively comment on any shortcomings.

You can contact: rapidxafs@rapid-xas.com

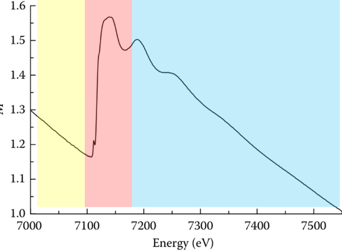

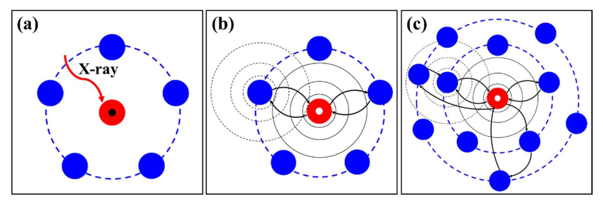

As a rule, the K-edge XAFS spectra of the classic Fe sample are presented (Figure 1). Obviously, the XANES part of the oscillation is strong, while the EXAFS part of the oscillation and frequency are much lower than that. The origin of this difference in spectral characteristics lies in the scattering pattern of XAFS. The basic physical process is shown in Figure 2: the red sphere in Figure 2a represents the central absorbing atom, and the black dots in it represent the electrons at the core level (the core energy level represents the 1s orbital of the 3d/4d transition metal or the 2p orbital of the 5d transition metal). When the sample is irradiated by X-rays, the incident photon excites the electrons at the core level of the central atom, leaving an electron hole, as shown by the white dot in Figure 2b. Due to the wave-particle duality, the excited electrons will spread outward in the form of waves (as shown in the black solid circle in Figure 2b), and the outgoing electron wave will meet the surrounding neighboring atoms and be scattered, and the scattered electron wave and the outgoing electron wave will meet somewhere between the central atom and the neighboring atoms, thus interfering. If the interference is coherent, then the absorption of X-rays is enhanced, which appears as a peak in the XAFS spectrum, and if the interference is destructive, it appears as a trough. In the case of out-of-scatter in a straight line-out, it is called single-scattering (Fig. 2b), and its oscillatory intensity is relatively weak, which is the physical origin of EXAFS, and in the case of out-of-scatter-rescatter, this process is called multiple scattering (Fig. 2c), which is the physical origin of XANES. These are the basic physical processes of XAFS. Next, let's learn the basic formula of EXAFS.

Figure 1. K-side XAFS spectra of Fe samples from Fe samples

Figure 2. XAFS generation mechanism

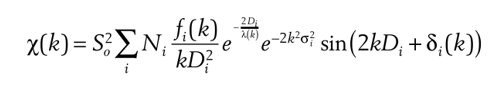

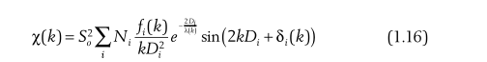

EXAFS fitting is currently the most widely used analytical method in the field of chemistry and materials, so learning the basic formula of EXAFS is very important for subsequent fitting. First, let's list the basic formula for EXAFS:

Isn't it tedious? It doesn't matter, today's study will lead you to dismantle it completely. The above formula is also our common formula for k-space, of course, without adding k weights. There may be beginners who don't pay much attention to the k-space, but the k-space is the root of EXAFS, and all subsequent processing is based on the deformation of the k-space. Once you have mastered the k-space, it will be easy to understand the R-space.

Before that, let's review the wavelength l, momentum p, and other related knowledge of electrons. Equation 1.1 describes the relationship between the wavelength and momentum of an electron:

where h is Planck's constant. If we set the atomic spacing D between the central atom and one of the neighboring atoms, then the following conditions must be met in order for the outgoing electron wave and the scattered electron wave to coherently interfere in the middle position

That is, the distance traveled by the outgoing and scattered electrons is an integer multiple of the wavelength of the electron wave. There may be a question here: why 2D? That's because the electron wave starts from the central atom, then reaches the neighboring scattered atom, is scattered back, and meets the outgoing electron halfway, and the sum of the distance traveled by the outgoing electron wave and the scattered electron wave is 2D. In this case, we assume that in the EXAFS process, the electron wave generated by the X-ray excitation of the central atom is a plane wave, and the interface during flat scattering is a soft boundary (without changing the phase), then the absorption probability can be obtained by the following formula:

When Equation 1.2 is satisfied, the absorption probability in Equation 1.3 will be maximum. That is to say, when interference occurs, the absorption probability is the strongest, and it will appear as a peak on the XAFS spectrum. At this time, the wavelength l is on the denominator, which is difficult to parse, so we introduce the concept of wavenumber:

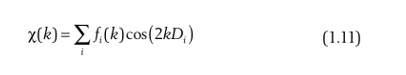

The wavenumber K can be understood as how many wavelengths are included in the length of 2p. Bringing Equation 1.4 into Equation 1.3 evolves to:

Reading this, you may not be very familiar with k, so the next few formulas will lead you to play with k thoroughly. First, if we bring Equation 1.4 into Equation 1.1, it will be transformed as:

The momentum p can be related to the kinetic energy T of the electron:

where me refers to the mass of the electron. So how does the kinetic energy T come about? At this time, it is necessary to mention the theory of the photoelectric effect proposed by Einstein: after the electron is shot out by a photon, the kinetic energy of the electron is equal to the energy of the photon minus the binding energy of the electron, that is

where E is the energy of the X-ray photon, and E0 is the binding energy of the electron, which can also be understood as the energy of the absorption edge. Combine equations 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8 with the following:

This is also the famous E➝k conversion formula.

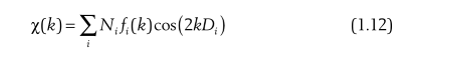

Let's go back to Equation 1.5, and we'll continue to enrich this formula. As you may have noticed, the absorption probability c is proportional to the electron wave interference formula that follows it, rather than "=", because we do not take into account the scattering power of the neighboring atoms around the central atom. The scattering ability of each atom is different, which is affected by the atomic number, atomic size, electron number, etc. Therefore, we need to substitute the scattering factor f(k), which is also a characteristic of the atomic species, and we also get the atomic type by obtaining f(k):

Of course, all the above derivations are based on the case that there is only one scattered atom around the central atom, and it needs to be considered that there are multiple scattered atoms, for example, in a chloroplatinic acid molecule, there are both Cl and O around Pt, so the formula evolves as:

That is, the scattering probability of each scattered atom and the central atom is added. Of course, there may be the same type of scattering atoms at the same distance around the central atom, for example, in iron oxide, there are exactly 6 O atoms evenly arranged around Fe, at this time, we do not need to add the scattering of these 6 O atoms one by one, we only need to multiply the number of atoms N:

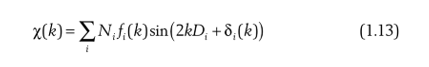

From Equation 1.12 we can see that the coordination number can be obtained by fitting the EXAFS formula. At the beginning, we assumed that the boundary of the nearest atom is a soft boundary, and in reality there is no soft boundary, that is, the phase must change, so we add a phase factor to the above formula:

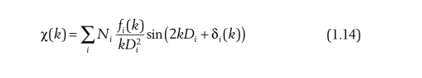

In addition, we also assume that the outgoing electron wave is a plane wave, but the atom is spatial and three-dimensional, and the outgoing electron wave must be transmitted in all directions, that is, the outgoing electron wave is a spherical wave:

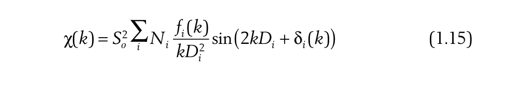

We also need to consider the attenuation of the peak strength caused by the harmonics of the monochromator and the error of the ionization chamber during the line station test, so we need to substitute the amplitude attenuation factor at the beginning of the formula:

The formula is getting more and more complicated, but is it clear to deduce it step by step?

We need to come up with the concept of the mean free path l(k), where the average free path is the average distance traveled by an electron after it has been shot out without any reaction. We know that after an electron is shot by a photon, there will be a variety of reactions, such as the change of electron direction, the electron is inelastically scattered, the outer electron fills the inner electron hole, etc., therefore, the average free path can be understood as the lifetime (length) of an electron, when the longer the length, the less the attenuation to Equation 1.15:

Here, we use an e-exponent to describe it with a power of -2D/l, which can be understood as the attenuation effect on the absorption probability at a certain length of free path. Imagine that when the average free path is infinite, this constant exponent tends to be close to 1, which has no effect on the absorption probability.

The last parameter to consider is thermal disorder. Even if the atoms are not fixed and immobile in solid materials, they will always vibrate within a certain and limited range, so the disorder of the material caused by this vibration is thermal disorder. Thermal disorder S2 is also known as mean square radial displacement, i.e., S2=(r-r0)2, where r0 is the average theoretical bond length. At this point, you can understand that the disorder degree is actually the disorder of the bond length, and the disorder of the bond length leads to the decay of the absorption probability:

This is the most comprehensive formula of EXAFS, and it is also the most fundamental basis on which the current data fitting is based. There is also a lot of hidden information to be obtained from this formula, which we will learn slowly in the future.